Kitsune Symbolism and Meaning

The Fox as a Liminal Spirit in Japanese Culture

In Japanese folklore, the kitsune is not a character in the usual sense. It is a condition. A state of being that exists between categories. Between animal and spirit, illusion and truth, control and surrender.

Kitsune does not represent a fixed moral idea. It represents movement. Change. The instability of perception itself. This is why the fox appears so often in stories that deal not with good and evil, but with transformation, self-deception, and awakening.

From a symbolic perspective, kitsune belongs to the same category as gates, mirrors, and masks. It marks a transition rather than a destination.

Two Faces of Kitsune: Yako and Zenko

Kitsune symbolism is traditionally divided into two main expressions. This division is essential for understanding the depth of the image.

Yako - the Wild Fox

Yako, often described as field or wild foxes, embody uncontrolled intelligence. These are the kitsune associated with witchcraft, possession, illusions, and deception. Yako do not follow moral codes. They test humans by exposing weakness rather than punishing wrongdoing.

Symbolically, yako represent knowledge without discipline. Awareness without responsibility. They are dangerous not because they are evil, but because they reveal what people prefer to hide from themselves.

In this sense, yako function as a mirror rather than an enemy.

Zenko - the Fox of Inari

Zenko are the benevolent manifestation of kitsune, serving Inari Ōkami. These white foxes are associated with rice, fertility, craftsmanship, prosperity, and protection.

Zenko do not deceive. They guide. Their symbolism is tied to balance between material effort and spiritual alignment. Rewards come not through shortcuts, but through patience, consistency, and respect for natural order.

Where yako destabilize, zenko stabilize.

One Nature, Different States

It is a mistake to see yako and zenko as separate beings. They are expressions of the same nature at different stages.

A kitsune evolves. With time, discipline, and experience, its energy refines. The appearance of multiple tails does not signify power in a physical sense, but accumulated understanding. The fox becomes less reactive and more precise.

This idea closely aligns with Zen thought. Identity is not fixed. Meaning is not assigned once. Transformation is continuous.

Kitsune does not choose a side. It moves along a path.

Kitsune Within The Symbolic Way

This is where kitsune fits naturally within The Symbolic Way.

Symbolism in Japanese culture is never illustrative. It is reductive. It removes excess in order to preserve essence. The more powerful the symbol, the less it needs to explain itself.

Kitsune functions exactly this way. Its presence implies transformation without stating it. It suggests instability without dramatizing it. The fox does not teach directly. It creates conditions for realization.

Kitsune in Japanese Tattoo Culture

Despite its popularity, kitsune is one of the most misunderstood subjects in tattooing.

Tattooing is not illustration. It is composition, longevity, and restraint.

A realistic fox body is extremely difficult to translate into a tattoo that will age well. The expression relies on subtle facial anatomy, fine fur direction, and delicate tonal transitions. On skin, especially over years, these details lose clarity. What looks impressive at first often becomes visually unstable with time.

Because of this, I do not treat a literal fox image as the strongest solution, even when it is the client’s original request.

Bando Mitsugoro VI and Nakamura Fukusuke II in a Play re the Story of the Nine-Tailed Fox, 1863

Woodblock Print

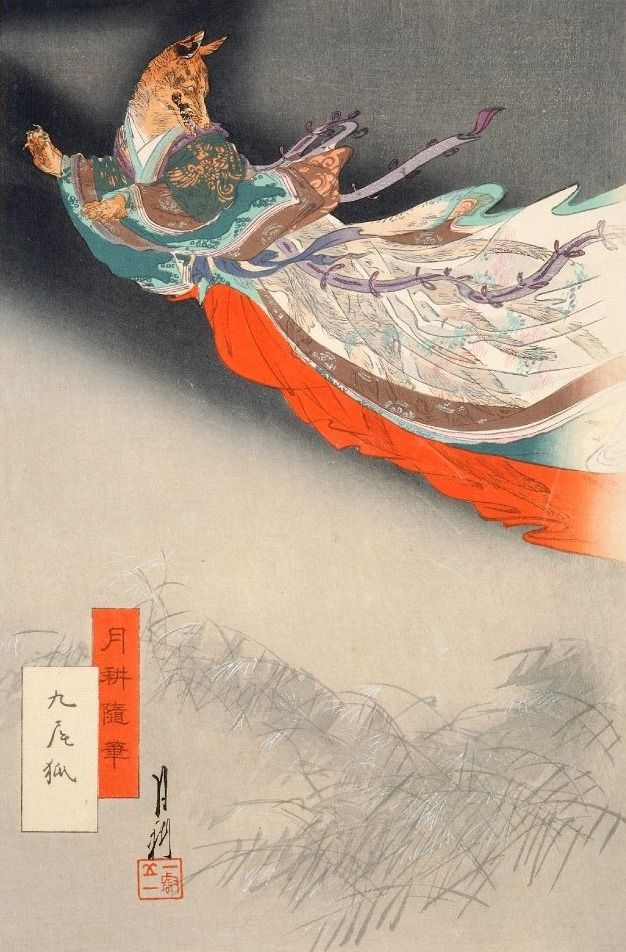

Nine-tailed Fox (Kyūbi no kitsune), from the series Gekkō’s Miscellany (Gekkō zuihitsu)

UTAGAWA KUNIYOSHI, 1798-1861

Tsumago (Tsumagome) Station.

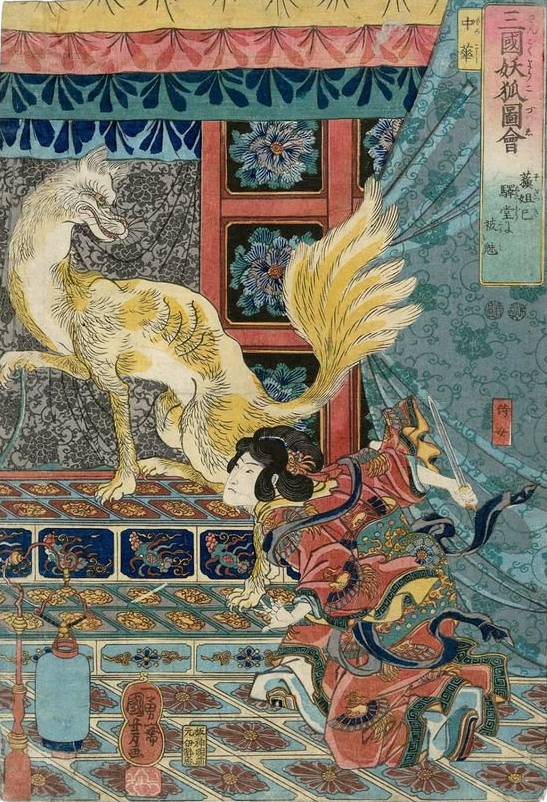

Kuniyoshi Utagawa, Daji Possessed by the Nine Tailed Fox Spirit in China

Utagawa Kuniyoshi,

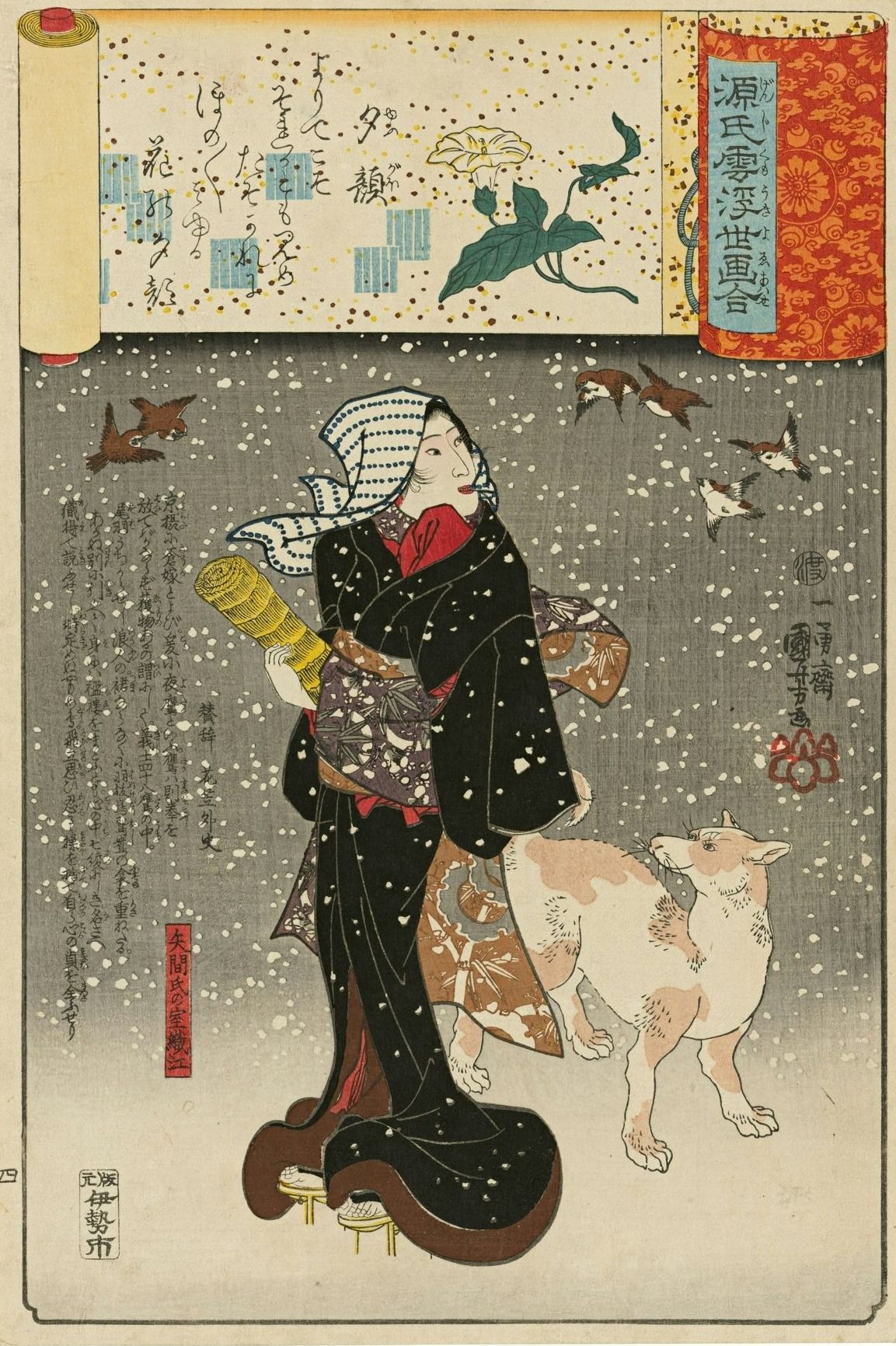

Prince Hanzoku Terrorized by a Nine-Tailed Fox, from the series Japanese and Chinese Parallels to Genji

Ichimura Kakitsu IV as Tamamo no mae, 1865

by Toyokuni III/Kunisada (1786 - 1864)

Japanese Print "Actor Nakamura Utaemon III as a Nine-tailed Fox, from the series Dance of Nine Changes (Kokonobake no uchi)" by Toyokawa Yoshikuni

Japanese Print "Sangoku yoko zue 三国妖狐図会 (The Magic Fox of Three Countries)" by Utagawa Kuniyoshi

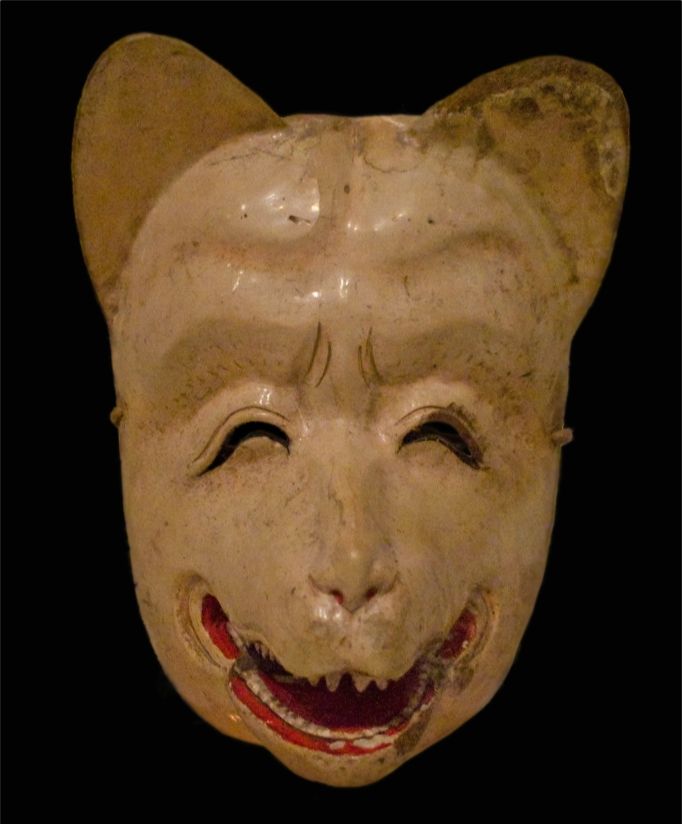

Why I Use the Kitsune Mask

In my work, I prioritize the kitsune mask from Noh theater over a literal fox depiction. This is not a stylistic preference. It is a symbolic decision. The mask removes biological fragility and leaves intention. It speaks about transformation without relying on realism. About identity without depicting a face. About presence rather than appearance.

In Noh theater, masks are never decorative. They are vessels. Emotion exists, but it is restrained. Meaning is present, but never explained. This aligns precisely with how tattoo imagery should function on the body.

When a client asks for a fox, my role is not to execute the request literally, but to translate the idea into a form that will remain readable, symbolic, and honest over time. In most cases, the kitsune mask does this better than the fox itself.

Symbol Over Image

Tattooing is not about showing everything. It is about choosing what must remain. Kitsune, when reduced to its essence, is not a fox at all. It is transformation made visible. The mask preserves that truth long after surface details fade.

That is why I choose it.

Connected Post

From symbol to skin.

See how the kitsune mask becomes a full sleeve composition, where structure, restraint, and symbolism take priority over literal imagery.

from The Symbolic Way

“Symbols speak where words fall silent.”